Baudelaire and the Alienation of the Artist

The artists and intellectuals of the second half of the 19th century were benefitting from the great increase in demand for culture from the new middle classes and from the great esteem that art and intellectual activity were held for the general public. But many bridled at the fact that they had to respond to the demands of a public that they felt was uncultured and philistine.

No one captured this alienation from the public more powerfully than Charles Baudelaire. In the two poems below he presents this sense of the artist lost in the new world of capitalist culture. This sense of alienation was a factor in the increased willingness of some authors to break with the official art world and move in very different directions.

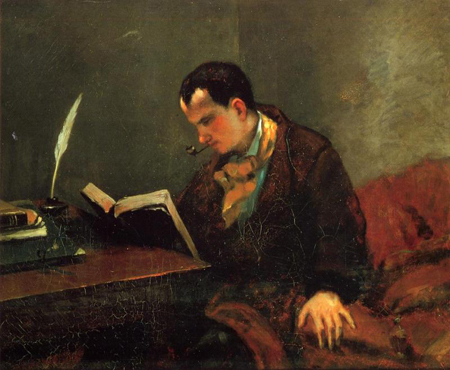

Gustave Courbet, Portrait of Baudelaire (1847)

The Albatross

Sometimes, to entertain themselves, the men of the crew

Lure upon deck an unlucky albatross, one of those vast

Birds of the sea that follow unwearied the voyage through,

Flying in slow and elegant circles above the mast.

No sooner have they disentangled him from their nets

Than this aerial colossus, shorn of his pride,

Goes hobbling pitiably across the planks and lets

His great wings hang like heavy, useless oars at his side.

How droll is the poor floundering creature, how limp and weak —

He, but a moment past so lordly, flying in state!

They tease him: One of them tries to stick a pipe in his beak;

Another mimics with laughter his odd lurching gait.

The Poet is like that wild inheritor of the cloud,

A rider of storms, above the range of arrows and slings;

Exiled on earth, at bay amid the jeering crowd,

He cannot walk for his unmanageable wings.

— George Dillon, Flowers of Evil (NY: Harper and Brothers, 1936)

At One O'Clock in the Morning

Alone, at last! Not a sound to be heard but the rumbling of some belated and decrepit cabs. For a few hours we shall have silence, if not repose. At last the tyranny of the human face has disappeared, and I myself shall be the only cause of my sufferings. At last, then, I am allowed to refresh myself in a bath of darkness! First of all, a double turn of the lock. It seems to me that this twist of the key will increase my solitude and fortify the barricades which at this instant separate me from the world. Horrible life! Horrible town! Let us recapitulate the day: seen several men of letters, one of whom asked me whether one could go to Russia by a land route (no doubt he took Russia to be an island); disputed generously with the editor of a review, who, to each of my objections, replied: 'We represent the cause of decent people,' which implies that all the other newspapers are edited by scoundrels; greeted some twenty persons, with fifteen of whom I am not acquainted; distributed handshakes in the same proportion, and this without having taken the precaution of buying gloves; to kill time, during a shower, went to see an acrobat, who asked me to design for her the costume of a Venustra; paid court to the director of a theatre, who, while dismissing me, said to me: 'Perhaps you would do well to apply to Z------; he is the clumsiest, the stupidest and the most celebrated of my authors; together with him, perhaps, you would get somewhere. Go to see him, and after that we'll see;' boasted (why?) of several vile actions which I have never committed, and faint-heartedly denied some other misdeeds which I accomplished with joy, an error of bravado, an offence against human respect; refused a friend an easy service, and gave a written recommendation to a perfect clown; oh, isn't that enough? Discontented with everyone and discontented with myself, I would gladly redeem myself and elate myself a little in the silence and solitude of night. Souls of those I have loved, souls of those I have sung, strengthen me, support me, rid me of lies and the corrupting vapours of the world; and you, O Lord God, grant me the grace to produce a few good verses, which shall prove to myself that I am not the lowest of men, that I am not inferior to those whom I despise.